Tune into the “Muckraker Report” on 910AM the Superstation from 11 a.m. to noon on Friday to hear more about this speech.

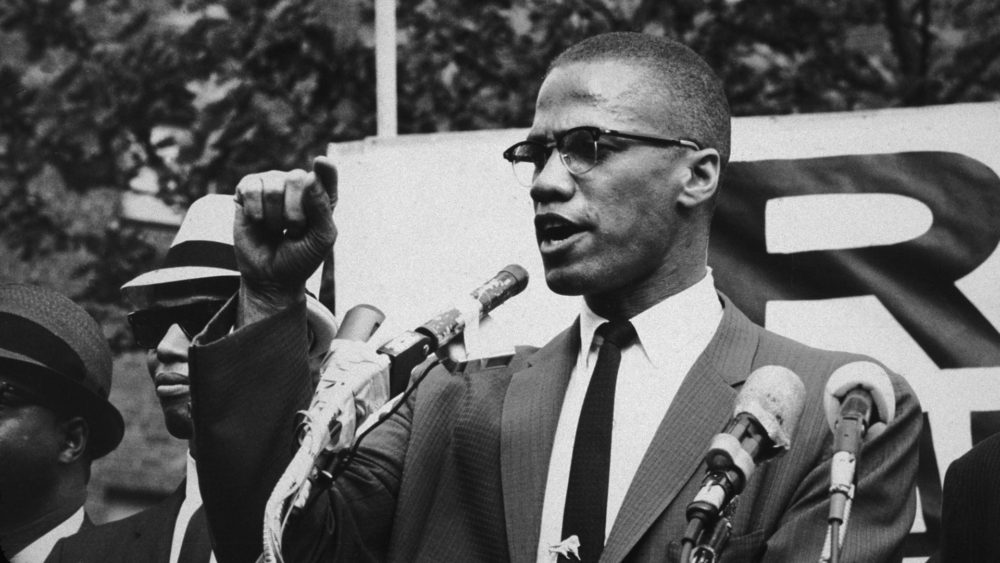

Black nationalism was on the rise in Detroit when Malcolm X delivered one of his most famous and influential speeches on this day in 1963 at King Solomon Baptist Church on the city’s west side, where he condemned the nonviolent civil rights movement and called for a “black revolution.”

At the time, Rev. Albert B. Cleage and other black activists were seeking to build a revolutionary movement in Detroit because they had become exceedingly pessimistic that white people would willingly help African Americans advance.

To promote black nationalism, Cleage sponsored a conference at King Solomon Baptist Church, where Malcolm X concluded the gathering of 3,000 people with his momentous “Message to the Grassroots,” widely considered one of the most influential speeches in the 1960s and a turning point in his career.

Mainstream black ministers in Detroit, including Bishop C.L. Franklin, tried to prevent Malcolm X from delivering the Nov. 10, 1963 speech, arguing that “separatist ideas can do nothing but set back the colored man’s cause.” But they were unsuccessful.

During the speech, Malcolm X called on black people to unite against white oppression and denounced the the mainstream civil rights movement as naive and ineffective. He called the previous summer’s March on Washington, led by Martin Luther King Jr., “a farce,” “a takeover” and “a circus.”

During the speech, Malcolm X called on black people to unite against white oppression and denounced the the mainstream civil rights movement as naive and ineffective. He called the previous summer’s March on Washington, led by Martin Luther King Jr., “a farce,” “a takeover” and “a circus.”

buy acticin online myindianpharmacy.net/acticin.html no prescription

Malcolm X, who at the time was the second most powerful black Muslim behind Elijah Muhammad, favored a more militant approach to racial equality, rejecting integration and nonviolence. Instead, he called for a revolution against white people and promoted a black nation separate from the U.S.

“You don’t have a peaceful revolution. You don’t have a turn-the-other-cheek revolution. There’s no such thing as a nonviolent revolution,” Malcolm X said. “Revolution is bloody, revolution is hostile, revolution knows no compromise, revolution overturns and destroys everything that gets in its way. And you, sitting around here like a knot on the wall, saying, ‘I’m going to love these folks no matter how much they hate me.’ No, you need a revolution. Whoever heard of a revolution where they lock arms, singing ‘We Shall Overcome?’ You don’t do that in a revolution. You don’t do any singing, you’re too busy swinging.”

Malcolm X tried to unite black people behind a common cause – ending white supremacy by any means necessary.

buy actos online myindianpharmacy.net/actos.html no prescription

“We have a common enemy,” he said. “We have this in common: We have a common oppressor, a common exploiter, and a common discriminator. But once we all realize that we have this common enemy, then we unite on the basis of what we have in common. And what we have foremost in common is that enemy – the white man. He’s an enemy to all of us. I know some of you all think that some of them aren’t enemies. Time will tell.”

In many ways, the speech was Malcolm X’s answer to King’s “I Have a Dream,” delivered several months earlier.

Malcolm X argued that black liberation required the redistribution of land and tied the black struggle for human rights to the fight against colonialism, comparing it to revolutionary movements in Africa and Asia.

The speech also compared field workers and house servants on slave plantations, arguing that the “house Negro” identified and sympathized with his master, while the “field Negro was beaten from morning to night. He lived in a shack, in a hut. He wore old, castoff clothes. He hated his master.”

Macomb X called Martin Luther King a “house Negro” – someone who sells out to white people.

“If the master got sick, the house Negro would say ‘What’s the matter, boss, we sick?’ We sick! He identified himself with his master, more than his master identified with himself,” Malcolm X said.

buy adalat online myindianpharmacy.net/adalat.html no prescription

The speech was his last major address as a member of the Nation of Islam. A few weeks after the speech, the Nation of Islam’s leader, Elijah Muhammad, silenced Malcolm X after he said the assassination of President John F. Kennedy was simply “the chickens coming home to roost.”

In April of 1964 Malcolm X returned to King Solomon, delivering his famous “The Ballot or the Bullet” speech in which he encouraged black people of all faiths and backgrounds to resist oppression.

More than a half century later, King Solomon Baptist Church, led by Rev. Charles Williams II, is still active in fighting for civil rights. In June, the church was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Martin Luther King also spoke at the church twice, once in 1958 and again in September 1963.

Motor City Muckraker is an independent watchdog funded by donations. To help us cover more stories like this, please consider a small contribution.

Steve Neavling

Steve Neavling lives and works in Detroit as an investigative journalist. His stories have uncovered corruption, led to arrests and reforms and prompted FBI investigations.